Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

The writer is the author of ‘Chip War’ and adviser to Vulcan Elements

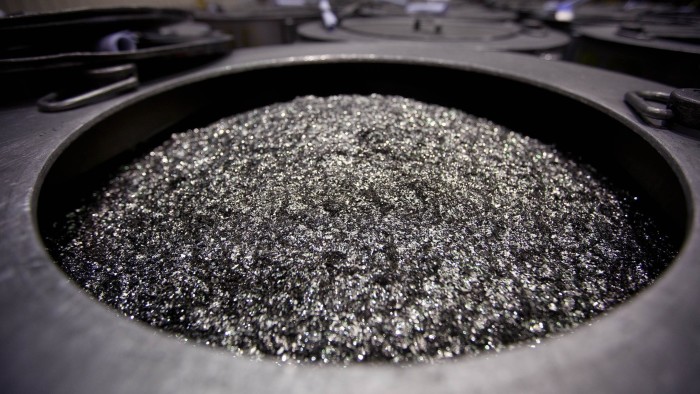

Shortly after Beijing announced new restrictions on exporting rare earth minerals and the specialised magnets they make, the world’s auto industry warned of shortages that could force factory closures. China’s skilful deployment of rare earth sanctions this spring was probably the key factor in forcing Washington to reverse its tariff rises on the country. They represent a new era of Chinese economic statecraft — evidence of a sanctions policy capable of pressuring not only small neighbours but also the world’s largest economy.

China has been a prolific user of economic sanctions in recent years, but many of its efforts have been blunt and only partially effective. Punitive measures have often been hidden and even officially denied. Chinese tour groups lost interest in visiting the Philippines, we were told; while Taiwanese pineapples couldn’t meet health standards and Chinese consumers simply didn’t want to buy Korean products.

Government-backed boycotts have imposed economic costs on China’s trade partners, but their record at achieving political goals has been mixed. They seem to have prevented some countries from hosting the Dalai Lama or challenging Beijing’s nine-dash line in the South China Sea. Yet they have proved less impactful when core national interests are at stake.

Australia didn’t cave when China cut wine purchases over foreign policy disputes, for example. Nor did South Korea remove a missile defence system it installed in 2016, despite China imposing sanctions and demanding its withdrawal. And China’s earlier sanctions against the US — including blacklisting defence companies and imposing licensing regimes on certain mineral exports — have been more political signal than economic substance.

The new controls on exporting rare earth materials and magnets are different. In just a handful of weeks they threatened to shutter key factories across the auto industry — the largest manufacturing sector in most advanced economies. They also brought the US president to heel on his signature initiative: the trade war.

The White House thought it had achieved escalation dominance. Its theory was that sky high tariffs would be so costly that Beijing would have no hope but to negotiate. In fact, China’s leaders could swallow the political cost of tariffs. But Washington couldn’t ignore the loss of rare earth materials and its impact on auto companies.

Why did these sanctions prove so much more effective than prior efforts? Partly because Beijing has been improving its toolkit, building a legal regime to cut strategic exports and improve knowledge of trade partners’ pain points. China has even made this extraterritorial, demanding that companies in other countries not use Chinese minerals to make products for the US defence industry. Beijing bet that other major trading partners would not blame it for the rare earth restrictions but instead push Washington to roll back tariffs.

Indeed, since April, Chinese exports of rare earth minerals and magnets have fallen not only to the US, but to other major trading partners such as Japan and South Korea. Indian automakers have cut production in the face of materials shortages. European Commission president Ursula von der Leyen brought a rare earth magnet to the June G7 meeting to call for more non-China production. The EU is prioritising rare earth exports in its diplomacy with China.

This broad global impact suggests that China’s ability to precisely target rare earth restrictions may still be limited. It’s harder to restrict resale of commodities like rare earth oxides than, say, jet engines or chipmaking equipment. If China wanted only to cut rare earth materials from reaching the US it might struggle to do so. Companies in other countries could continue to quietly sell to American customers.

Still, the most striking aspect of China’s weaponisation of rare earths is how unprepared western governments and companies were. Even those who cannot name a single rare earth element know that China dominates their production. Nevertheless, over the decade and a half since China first cut rare earth exports to Japan in 2011, the west has failed to find new suppliers.

Some modest steps were taken. Korea expanded its stockpiles. Japan invested in Australian mines. Yet most western governments devised critical minerals strategies and then chose not to fund them. Manufacturers speak of resilience yet some keep only a week’s supply of rare earth magnets in their inventories. This is a weapon they have been staring at for decades. They should not have been surprised when Beijing finally pulled the trigger.

https://www.ft.com/content/77eabb2b-e422-4863-86e1-1a6948ecf368