Godwin Bebe Okpabi remembers the discovery of oil in his community of Ogale in Nigeria’s Niger Delta as a halcyon period in his life. Modest development followed as paved roads were laid and British Land Rovers sped through villages that were unused to cars. Children mingled freely with the oil workers and took pride in helping whenever the vehicles got stuck.

But the positive feeling did not last long. Almost immediately after Shell and other international companies began extracting oil, Okpabi says there was a noticeable change in the area, evidenced by wilting fruits on contaminated farmlands and dead birds and animals.

“Families used to cultivate their own food,” Okpabi, a US-educated criminologist who is now king of Ogale, says of his community before the oilmen came. There has been “a complete disappearance of a way of life and our ecosystem”, he adds.

Now as the foreign companies that built Nigeria’s oil industry are exiting the polluted Niger Delta for easier, more lucrative operations offshore in the Gulf of Guinea or in other countries, communities and rights groups want to know what will become of the environmental mess left behind.

In the past two years Shell, Exxon, Eni, Equinor and China’s Addax are among companies that have announced plans to divest their onshore assets. In most cases, they are selling to Nigerian groups who will continue to operate the wells and take on responsibility for cleaning up past oil spills.

Supporters of the divestment process, including government officials and local oil executives, frame the sale as a positive step in the indigenisation of the country’s oil sector, which represents about 5 per cent of GDP and over 90 per cent of exports. Nigerian companies, they say, will be better placed to manage the complex web of political interests, criminality and community grievances that has made operating in the Niger Delta so challenging. Critics say oil majors are passing the buck to local groups that are likely to make things worse.

“It is insufficient for international oil companies to leave without cleaning up,” says Olanrewaju Suraju, head of the human rights project at the Human and Environmental Development Agenda (Heda Resource Centre). “They’re running away from responsibilities and liabilities and going offshore where nobody can see clearly what’s going on.”

No international company is facing greater scrutiny than Shell. For many Nigerians, the brand is synonymous with the country’s oil industry. The Anglo-Dutch group was granted its first exploration licence to prospect for oil in Nigeria in 1938 and drilled the country’s first successful well in 1956 in the small community of Oloibiri, some 100km west of Ogale.

Last month, the Nigerian regulator said the planned $1.3bn sale of its 68-year-old onshore oil production business, Shell Petroleum Development Company of Nigeria (SPDC), to a mainly local consortium known as Renaissance Africa Energy did not pass the “regulatory test”.

The announcement has left Europe’s biggest energy company in limbo: unwilling to keep managing the issues that make operating in the Niger Delta so difficult, but so far unable to leave.

“There is no specific timeframe around this,” Shell chief executive Wael Sawan tells the Financial Times. “This is with the government to be able to make sure they feel confident they have a deal that they can bless.”

The sale of SPDC was always going to be emotive for Nigeria. It is the biggest and oldest oil company in the country, operating 3,173 kilometres of pipelines and flow lines that cross a vast swath of the Niger Delta, connecting 263 producing oil wells, 56 producing gas wells, six gas plants, two oil export terminals and one power plant.

The assets are part of the so-called SPDC JV, an unincorporated joint venture that produces as much as 30 per cent of Nigeria’s oil and gas. Shell’s SPDC owns 30 per cent, the state-owned Nigerian National Petroleum Company (NNPC) holds 55 per cent and TotalEnergies and Agip control 10 per cent and 5 per cent, respectively. But to most observers the operations of the SPDC JV are indistinguishable from those of Shell.

5%The estimated contribution of the oil sector to Nigeria’s GDP

Under the terms of the proposed sale, SPDC will remain intact and continue to operate the joint venture. Its new owners, Renaissance, will be responsible for the company’s ongoing contribution to the remediation of past environmental damage.

“After decades as a pioneer in Nigeria’s energy sector, SPDC will move to its next chapter under the ownership of an experienced, ambitious Nigerian-led consortium,” Shell director Zoë Yujnovich said in January. Renaissance includes Switzerland-based Petrolin and four Nigerian oil producers, ND Western, Aradel Holdings, First E&P and Waltersmith, some of which have been operating in the Niger Delta for 20 years.

Current and former Shell executives say the company’s full exit from Nigeria’s onshore oilfields had been inevitable. Shortly after former boss Ben van Beurden became chief executive in 2014, he took a view that the interconnected problems of organised oil theft, environmental damage and community grievances in the Niger Delta had made onshore operations essentially unmanageable, according to those executives. Shell initially worked on divesting individual blocks but ultimately decided that a full sale of its SPDC stake was required.

Shell quickly identified the Renaissance consortium as a preferred buyer, but met resistance from the Nigerian government, Shell executives told Ben Llewellyn-Jones, then British deputy high commissioner to Nigeria, according to minutes from a September 2022 meeting.

State-owned NNPC had told Shell “there is no one able to buy and run the assets”, the commissioner recalled in the minutes, which were obtained via a freedom of information request. Shell countered that the right consortiums did exist and offered to provide technical support to the eventual buyer, he wrote.

Former Shell executives involved in the discussions at the time said it appeared that the government had never considered Shell might one day leave the delta and assumed the proposed sale was just a negotiating strategy.

Ongoing Nigerian court cases, brought by local plaintiffs over responsibility for past spills, then blocked the sales process for more than a year until Nigeria’s Supreme Court ruled in January that the divestment could proceed.

Still, the announcement of the sale to Renaissance stunned the sector, marking, more than any other planned divestment, the end of an era.

Even many of the company’s own employees were surprised by the decision to sell SPDC in its entirety and the Nigerian federal government was, once again, resistant.

“The [Federal Government] is negotiating for them not to sell, but Shell have told them it cannot be reversed,” the UK foreign office wrote following meetings with Shell executives at the end of January.

Some of Shell’s problems in the delta have been of its own making.

In 1993, SPDC stopped drilling in Ogoniland, where Ogale is situated, as community tensions threatened to boil over. They duly did two years later following the execution of environmental activist Ken Saro-Wiwa and eight others by Nigeria’s military government on trumped-up charges of murder.

The case has haunted Shell ever since. The company has always rejected any accusation of complicity in their deaths but was sued by the families of the victims in a US court. It reached a $15.5mn settlement in 2009 while denying any wrongdoing. “The Shell Group, alongside other organisations and individuals, appealed for clemency to the military government in power in Nigeria at that time, but to our deep regret those appeals went unheard,” the company said in a statement.

FT Edit

This article was featured in FT Edit, a daily selection of eight stories to inform, inspire and delight, free to read for 30 days. Explore FT Edit here ➼

Despite stopping work in Ogoniland over 30 years ago, SPDC pipelines still criss-crossing the region have continued to be found responsible for spills. In 2011, the UN’s Environment Programme found that the contamination of drinking water there was an “immediate danger to public health” and called on SPDC to start a clean-up operation. The discoloured water that stinks of benzene, a chemical that occurs naturally in crude oil, remains unfit for human consumption.

In Bodo, a small town close to Ogale, two catastrophic spills occurred in 2008 when a major SPDC pipeline ruptured twice, dumping nearly 600,000 barrels of crude, or roughly half of Nigeria’s daily crude production, into farmlands and rivers. About 1,000 hectares of mangroves were destroyed, according to London law firm Leigh Day, which represented the community in a lawsuit against Shell. The group eventually paid more than $80mn in compensation after a lengthy legal wrangling that ended just as a trial was due to begin at London’s High Court.

There was another spill in 2012, according to the Bodo Mediation Initiative (BMI), a vehicle set up to foster dialogue between Shell and the community, largely bankrolled by the oil company.

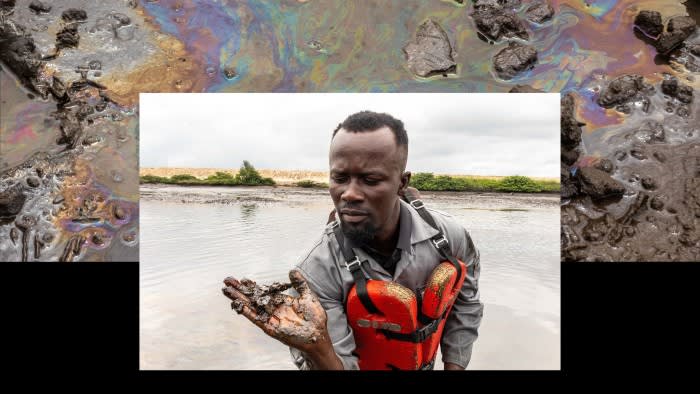

In the surrounding swamplands, accessible only by a rickety boat, the first phase of the clean-up, which involves the removal of surface contamination, has been deemed complete. The second stage of the process to remove and flush oil out of the soil is ongoing.

But a rainbow-like layer of oil on the water’s surface remains visible to the naked eye. Oil oozes out if a foot is dipped gently into the supposedly cleaned mangrove.

Boniface Dumpe, deputy project director of the BMI, says that some areas were “re-oiled” by illegal refineries set up during the year when the clean-up project was suspended due to community unrest. “Stakeholders should make sure the area is protected significantly,” he adds. “We need to make sure the areas that had been cleaned and certified cleaned will stay clean.”

In a statement, SPDC said that the clean-up effort at Bodo was 88 per cent complete, adding that it was “determined” to complete the remediation work “as soon as possible”.

The challenges in Bodo cut to the heart of the problem. When so many groups can be blamed for the environmental damage — the oil companies that drilled the wells and then failed to maintain the infrastructure amid rising insecurity, the criminal groups that illegally tap the pipelines, the politicians that profit from turning a blind eye — who is responsible for finding a lasting solution?

300,000Barrels of crude per day in Nigeria lost to theft, pipeline sabotage and other criminal activities

But the backlog of clean-up and maintenance is “not the biggest problem”, a former Shell executive with knowledge of the situation admits.

While major leaks have occurred due to ageing pipes or well infrastructure, most observers agree that the illegal tapping of pipelines is the larger issue.

In hindsight, Shell was probably too passive in the early 2000s when oil theft started, the executive says. By the 2010s it had become “a shadow economy that was impossible to stamp out”.

Authorities estimate that Nigeria still loses as much as 300,000 barrels of crude per day to theft, pipeline sabotage and other criminal activities, despite a recent improvement in the security outlook. For comparison, Nigeria produced 1.3mn barrels per day of crude in September, according to Opec data.

“It is a big monster that is impossible to put back into the bottle,” the executive adds.

One of the reasons Shell persevered with SPDC for as long as it did is that gas produced from the SPDC JV’s onshore oilfields is needed to feed Nigeria LNG, which produces 7 per cent of the world’s liquefied natural gas.

Shell owns 25.6 per cent of the lucrative project and is the operator. It has sought to protect that plant’s gas supply by agreeing to provide additional financing to Renaissance of up to $1.3bn to fund SPDC’s share of the development of the joint venture’s gas resources.

That money will also be used to fund SPDC’s share of “specific decommissioning and restoration costs”, it said. However, the terms of the sale provide for SPDC’s new owners to be responsible for the remediation of any past spills.

“By preserving the full range of SPDC’s operating capabilities, the transaction has been designed to ensure that the company can continue to perform its role as operator and to meet its share of commitments within the joint venture,” Shell says on its website.

The company argues that this is preferable to dividing SPDC’s assets between several buyers, as some Nigerian interests have allegedly urged the government to do.

Divesting SPDC in its entirety has the added benefit of leaving “a very well run company with a lot of capability” intact, the former Shell executive says.

Nigerian NGOs have challenged this structure as inadequate. “The sale of SPDC should not be permitted unless local communities have been fully consulted; the environmental pollution caused to date by SPDC has been fully assessed; and funds have been placed by SPDC in escrow sufficient to guarantee that clean-up costs will be covered,” Isa Sanusi, Nigeria director of Amnesty International, and over 30 over civil society groups, said in April in a letter to the Nigeria regulator.

People familiar with Shell’s thinking say responsibility for cleaning up legacy spills has to remain with SPDC as it is the only entity capable of addressing them and that this work would be easily funded out of the company’s ongoing cash flow.

“I continue to have high confidence in the process and confidence in the way that we have set up the transaction that I think will serve Nigeria very well in the longer term,” Shell’s Sawan tells the FT.

Despite the anger towards the company in parts of the Niger Delta, some community leaders fear the pollution, corruption and criminality will get worse if SPDC has local owners. Shell is at least “mindful” of its international image, says Okpabi, the Ogale king. “The [Nigerian companies] only understand how to make money . . . and they will deal with us even worse,” he adds.

A local oil industry executive rejects the assertion that the new owners would be more likely to bully local communities, pointing to examples where divestment to Nigerian owners had improved community relations. “This is a complex dance that’s been happening for 50 years,” the executive says of the relationship between oil companies and communities. “Some of the reaction now is a fear of the unknown.”

Ultimately, the communities will have little choice. Whether or not the sale of SPDC to Renaissance gets approved, Shell is committed to divesting. Its seven decades in the Niger Delta will eventually come to an end and it will be up to the Nigerian government and the new owners to manage the interlinking problems better than Shell. If they do not, the leaks, sabotage and criminality will continue, oil will keep seeping into waterways and the communities will keep suffering.

“Has oil been good for the communities and the environment in the delta? The answer is no,” says another former Shell executive with extensive experience in Nigeria. “If Shell hadn’t been there and someone else was operating, I think it would have been worse.”

Okpabi is not as sanguine about Shell’s involvement. “The coming of oil exploration is a terrible story,” he says. “Even if we haven’t benefited financially, at least [our environment] shouldn’t be ruined. It’s a lose-lose situation for us.”

Cartography by Steven Bernard

https://www.ft.com/content/a9850445-50be-41e3-95f9-0238d7a0218b