Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

The writer is a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution and a former chief economist at the Institute of International Finance

The US election may be the start of a massive dollar rally, but markets have yet to realise this. In fact, without much clarity on what is coming, markets are currently doing a retread of price action after Donald Trump’s 2016 win. Expectations of looser fiscal policy are lifting growth expectations, boosting the stock market, while rising US interest rates vis-à-vis the rest of the world buoy the dollar.

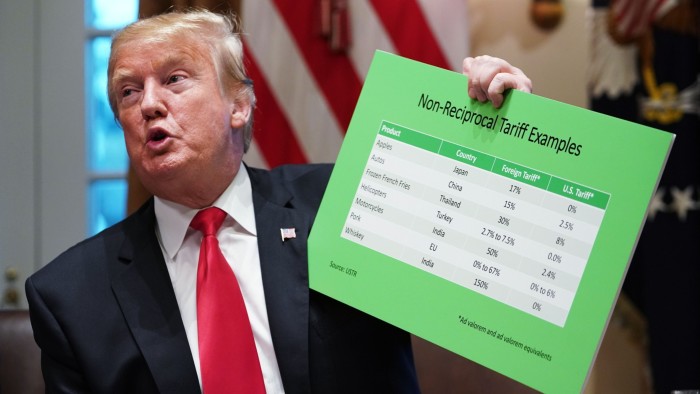

But, if the president-elect follows through on tariffs, bigger changes are coming. In 2018, after the US put a tariff on half of everything it imported from China at a 25 per cent rate, the renminbi fell 10 per cent versus the dollar, in what was almost a one-for-one offset. As a result, dollar-denominated import prices into the US were little changed and tariffs did little to disrupt the low-inflation equilibrium before the Covid-19 pandemic. The lesson from that episode is that markets trade tariffs like an adverse terms-of-trade shock: the currency of the country subject to tariffs falls to offset the hit to competitiveness.

If the US imposes further and perhaps much larger tariffs, the case for renminbi depreciation is urgent. This is because China has historically struggled with capital flight when depreciation expectations take hold in its populace. When this happened in 2015 and 2016, it sparked big outflows that cost China $1tn in official foreign exchange reserves.

Maybe restrictions on capital flows have been tightened since then, but the main lesson from that episode is to allow a front-loaded, large fall in the renminbi, so that households cannot front-run depreciation. The larger US tariffs are, the more important this rationale becomes. Take the case of a 60 per cent tariff on all imports from China, a number the president-elect floated during the campaign. Factoring in tariffs already in place from 2018, this could require a 50 per cent fall in the renminbi versus the dollar to keep US import prices stable. Even if China imposes retaliatory tariffs, which will reduce this number, the scale of needed renminbi depreciation is likely unprecedented.

For other emerging markets, such a large depreciation will be seismic. Currencies across Asia will fall in tandem with the renminbi. That in turn will drag down emerging markets currencies everywhere else. Commodity prices also will tumble for two reasons. First, markets will see a tariff war and all the instability that comes with it as a negative for global growth. Second, global trade is dollar-denominated, which means emerging markets lose purchasing power when the dollar rises. Financial conditions will — in effect — tighten, which will also weigh on commodities. That will only add to depreciation pressure on the currencies of commodity exporters.

In such an environment, the large number of dollar pegs in emerging markets are especially vulnerable. Depreciation pressure will become intense and many pegs will be at risk of explosive devaluations. Notable pegs include Argentina, Egypt and Turkey.

For all these cases, the lesson is the same: this is a uniquely bad time to peg to the dollar. The US has more fiscal space than any other country and seems determined to use it. That is dollar positive. Tariffs are just one manifestation of deglobalisation, a process that shifts growth from emerging markets back to the US. That is also dollar positive. Finally, elevated geopolitical risk is making commodity prices more volatile, increasing the incidence of economic shocks. That makes fully flexible exchange rates now more valuable than in the past.

The good news is that the policy prescription for emerging markets is clear: allow your exchange rate to float freely and act as an offset to what could be a very large external shock. The pushback to this idea is that large depreciations can boost inflation, but central banks in emerging markets have become better at tackling this. They mostly navigated the Covid inflation shock better than their G10 counterparts, raising interest rates earlier and faster. The bad news is that another major surge in the dollar could do lasting damage to local currency debt markets across emerging markets.

These economies have already suffered because the huge rise in the dollar over the past decade wiped out returns for foreign investors when converting back into their home currencies. Another big rise in the dollar will further damage this asset class and push up interest rates in emerging markets. This makes it all the more imperative for these economies to budget wisely and pre-emptively.

https://www.ft.com/content/c9617ae5-8b8d-450d-a45f-6e3b539225a9