Taipei, Taiwan – After beginning 2023 with a bang, China’s economic system had a bumpy restoration over the previous 12 months.

The Chinese economic system’s precarious footing appears set to proceed into 2024, as deep-seated structural points and Chinese President Xi Jinping’s consolidation of political management threaten to dampen progress.

China’s reopening after the lifting of its harsh “zero-COVID” restrictions in January coincided with difficult financial circumstances abroad, as hovering inflation made customers much less inclined to purchase Chinese items.

At house, Chinese customers had been cautious to start out spending once more after almost two years of lockdowns and border closures.

In July, China bucked the worldwide pattern and entered a interval of deflation, which it struggled to exit within the second half of the 12 months.

Prices in November fell 0.5 % 12 months on 12 months – the sharpest drop in three years.

China’s actual property disaster continued to roll on as extra builders teetered getting ready to default and residential gross sales remained at half their December 2020 ranges – spelling bother for an economic system by which property accounts for round 30 % of gross home product (GDP) and almost 70 % of family wealth.

While the International Monetary Fund (IMF) expects the Chinese economic system to complete the 12 months at 5.4 % progress, economists predict a slowdown in 2024 and past amid structural issues reminiscent of document ranges of debt and a low delivery charge.

Foreign traders have voted with their pocketbooks.

China posted a overseas funding deficit of $11.8bn within the three months to September – the primary time overseas companies pulled more cash in a foreign country than they put in since information started.

Capital outflows in September hit $75bn, in accordance with Goldman Sachs, the best determine in seven years.

Although China has confronted financial slowdowns earlier than, the size of challenges dealing with the economic system has centered consideration on Xi’s management.

Breaking with the collective-based decision-making of previous leaders like predecessor President Hu Jintao, Xi has concentrated energy in his palms, prioritised political management over the economic system, and additional blurred the strains between the Chinese state and the ruling Communist Party.

Part of that shift concerned decreasing the affect of the Chinese premier, formally the second-highest-ranking official in China’s political system, whose position has historically concerned setting the tone of financial coverage.

Under Xi’s management, financial coverage has emphasised “stability” and the aim of “common prosperity” to shut the hole between the haves and have-nots and the rich coast and inland provinces.

Such concentrated decision-making doesn’t at all times bode properly for the economic system, Chenggang Xu, a senior analysis scholar on the Stanford Center on China’s Economy and Institutions.

“When the premier managed the economy, he would rely on experts in different areas, so it depended very much on the quality of the experts,” Xu instructed Al Jazeera.

“But since Xi Jinping’s rule, he [no longer] trusts the premier, and he took over the power to manage the economy directly. So who’s the expert? There’s no experts.”’

Carsten Holz, an skilled on the Chinese economic system on the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, mentioned the political local weather has made it tough to acquire a transparent understanding of the nation’s financial issues.

“The all too often near-anarchic environment of the past two decades has led to such features as an over-indebted property sector, a partially insolvent wealth management system, murky local government finances, commercial banks loan books of questionable quality, and an exploitative elite ranging from entrepreneurs to managers of ‘state-owned’ enterprises and government and Party cadres,” Holz instructed Al Jazeera.

“No authority can grasp the full extent of the individual economic problems, let alone their interdependencies.”

In the previous few years, Xi has additionally overseen a far-reaching regulatory crackdown on industries starting from tech to monetary providers and personal schooling.

One main change in 2023 was the institution of the National Financial Regulatory Administration, which is immediately overseen by China’s cupboard, to take over the China Banking and Insurance Regulatory Commission’s position in regulating the monetary business.

Gary Ng, an economist at Natixis in Hong Kong, mentioned such reforms have been essential to fill in regulatory “grey areas”.

Other modifications, nevertheless, have rattled traders, together with an anti-espionage legislation that has raised questions concerning the legality of overseas companies doing consulting and enterprise intelligence work.

Earlier this 12 months, China investigated the consulting corporations Bain & Company and the Mintz Group – fining the latter $1.5m in August for “illegal business operations”.

“It’s a communist totalitarianism. It means that the Communist Party controls everything, including private firms, including foreign firms,” mentioned Xu.

“The reason the foreign firms are going to be purged is exactly because they are afraid of these firms not being controlled by [the Party]. If you surrender completely under their control, then you can operate.”

Under Xi, Beijing has additionally tried to set the course of its main industries, more and more choosing winners and losers as an alternative of leaving it to the market, Ng mentioned.

“Tencent and Alibaba were allowed to grow in the past because of the blessing of regulators, but right now, I think there is indeed a stronger state-led approach in terms of deciding what kind of industry does China want [and] where should the social or the general economic resources be deployed,” he mentioned.

Beijing’s rising involvement within the economic system can also be a priority for traders within the context of geopolitical flashpoints reminiscent of Taiwan, which Xi has pledged to “reunify” with China by 2049.

Chris Beddor, deputy China analysis director at Gavekal Research, mentioned that Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and subsequent sanctions on Moscow have been a wake-up name about geopolitical dangers.

“It’s a live-fire demonstration to Western investors,” Beddor instructed Al Jazeera.

“What happens, basically, when the United States government does not like a country, and that means that you need to pull up quickly, and you will probably [find] there’s a lot of money in that process, and it’s quite painful.”

For Xi, discovering new drivers of financial progress can be a significant problem.

An estimated 60 to 80 million residences throughout China stay empty, and one other 20 million are reportedly unfinished, in accordance with Nomura, a Japanese funding financial institution.

According to a report from the Brookings Institution, China’s economic system is so reliant on actual property that if the sector had been to say no by one-third, 10 % of Chinese manufacturing must get replaced by new actions.

While Beijing has prevented a significant Western-style bailout for the sector, seemingly content material to let some corporations fail as a cautionary story, there have been indicators of a current shift in coverage amid experiences that fifty builders had been positioned on a listing for presidency help.

“An area where you can see [Xi’s] thumbprints on the economy is a focus on industrial policy, and the vision that economic policymakers laid that we don’t need property, maybe even we don’t need exports as much any more,” Beddor mentioned.

“Those are the old drivers of growth. And instead, what we’re going to search for is new drivers of growth, especially in technology.”

Xi’s bid to scale back China’s reliance on property has had combined outcomes.

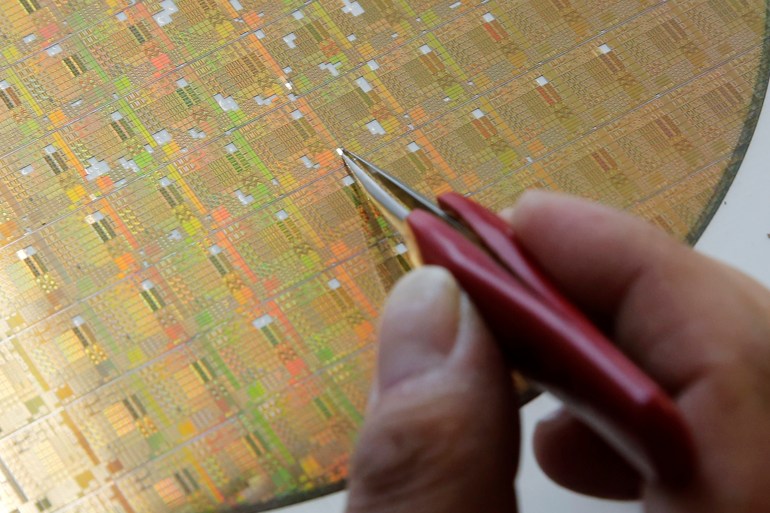

China’s electrical car and inexperienced power industries have made strides, whereas different sectors reminiscent of semiconductors have struggled to make headway.

In a bid to offset the influence of US sanctions, Beijing poured $29bn into its semiconductor business in 2019 – however the sudden inflow of funding was marred by experiences of widespread corruption and inefficiency.

A subsequent crackdown ensnared a raft of executives related to China’s flagship semiconductor funding fund.

Huge ranges of native authorities debt – amounting to $12.6 trillion, or 76 % of financial output in 2022, in accordance with the IMF – are one other problem dealing with policymakers in 2024.

In September, authorities allowed native governments to problem $137bn in bonds to repay the debt, and weeks later, ordered banks to reissue loans to native governments on account of mature in 2024 at decrease rates of interest.

Natixis’s Ng mentioned China has many instruments to take care of the native authorities debt problem, together with a excessive financial savings charge and the ability of the central authorities to “mobilise state resources” not readily accessible in different nations.

Others, together with score company Moody’s, are much less constructive.

Earlier this month, Moody’s downgraded Beijing’s credit standing from secure to detrimental, citing its bailout of indebted native governments, the actual property disaster and the nation’s shrinking inhabitants.

The score company reportedly instructed its staff in China to remain house forward of the announcement on account of fears of potential retaliation, in accordance with the Financial Times.

One factor most financial analysts can agree on is that China’s economic system is in want of great reform to offset slowing down.

Holz, the economist, mentioned that can be tough below Xi’s tightened management of the economic system.

“Going forward, economically we can expect to see more of what we have already seen in 2023: minor fiscal and monetary stimulus measures, many attempts at microeconomic problem solving through discretionary government interventions, and largely unsuccessful attempts to get on top of individual problems,” Holz mentioned.

“Appeasing foreign fears of PRC nationalism and militarism to attract foreign direct investment and to increase exports is also currently again on the agenda,” he mentioned, utilizing an acronym for the People’s Republic of China. “But, fundamentally, the system is stuck. Reform and development cannot move forward for fear of major problems surfacing from unexpected corners of the economy.”

https://www.aljazeera.com/economy/2023/12/22/after-bumpy-recovery-chinas-economy-faces-serious-headwinds-in-2024?traffic_source=rss