Nine years ago, one of the world’s leading artificial intelligence scientists singled out an endangered occupational species.

“People should stop training radiologists now,” Geoffrey Hinton said, adding that it was “just completely obvious” that within five years A.I. would outperform humans in that field.

Today, radiologists — the physician specialists in medical imaging who look inside the body to diagnose and treat disease — are still in high demand. A recent study from the American College of Radiology projected a steadily growing work force through 2055.

Dr. Hinton, who was awarded a Nobel Prize in Physics last year for pioneering research in A.I., was broadly correct that the technology would have a significant impact — just not as a job killer.

That’s true for radiologists at the Mayo Clinic, one of the nation’s premier medical systems, whose main campus is in Rochester, Minn. There, in recent years, they have begun using A.I. to sharpen images, automate routine tasks, identify medical abnormalities and predict disease. A.I. can also serve as “a second set of eyes.”

“But would it replace radiologists? We didn’t think so,” said Dr. Matthew Callstrom, the Mayo Clinic’s chair of radiology, recalling the 2016 prediction. “We knew how hard it is and all that is involved.”

Computer scientists, labor experts and policymakers have long debated how A.I. will ultimately play out in the work force. Will it be a clever helper, enhancing human performance, or a robotic surrogate, displacing millions of workers?

The debate has intensified as the leading-edge technology behind chatbots appears to be improving faster than anticipated. Leaders at OpenAI, Anthropic and other companies in Silicon Valley now predict that A.I. will eclipse humans in most cognitive tasks within a few years. But many researchers foresee a more gradual transformation in line with seismic inventions of the past, like electricity or the internet.

The predicted extinction of radiologists provides a telling case study. So far, A.I. is proving to be a powerful medical tool to increase efficiency and magnify human abilities, rather than take anyone’s job.

When it comes to developing and deploying A.I. in medicine, radiology has been a prime target. Of the more than 1,000 A.I. applications approved by the Food and Drug Administration for use in medicine, about three-fourths are in radiology. A.I. typically excels at identifying and measuring a specific abnormality, like a lung lesion or a breast lump.

“There’s been amazing progress, but these A.I. tools for the most part look for one thing,” said Dr. Charles E. Kahn Jr., a professor of radiology at the University of Pennsylvania’s Perelman School of Medicine and editor of the journal Radiology: Artificial Intelligence.

Radiologists do far more than study images. They advise other doctors and surgeons, talk to patients, write reports and analyze medical records. After identifying a suspect cluster of tissue in an organ, they interpret what it might mean for an individual patient with a particular medical history, tapping years of experience.

Predictions that A.I. will steal jobs often “underestimate the complexity of the work that people actually do — just as radiologists do a lot more than reading scans,” said David Autor, a labor economist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

At the Mayo Clinic, A.I. tools have been researched, developed and tailored to fit the work routines of busy doctors. The staff has grown 55 percent since Dr. Hinton’s forecast of doom, to more than 400 radiologists.

In 2016, spurred by the warning and advances in A.I.-fueled image recognition, the leaders of the radiology department assembled a group to assess the technology’s potential impact.

“We thought the first thing we should do is use this technology to make us better,” Dr. Callstrom recalled. “That was our first goal.”

They decided to invest. Today, the radiology department has an A.I. team of 40 people including A.I. scientists, radiology researchers, data analysts and software engineers. They have developed a series of A.I. tools, from tissue analyzers to disease predictors.

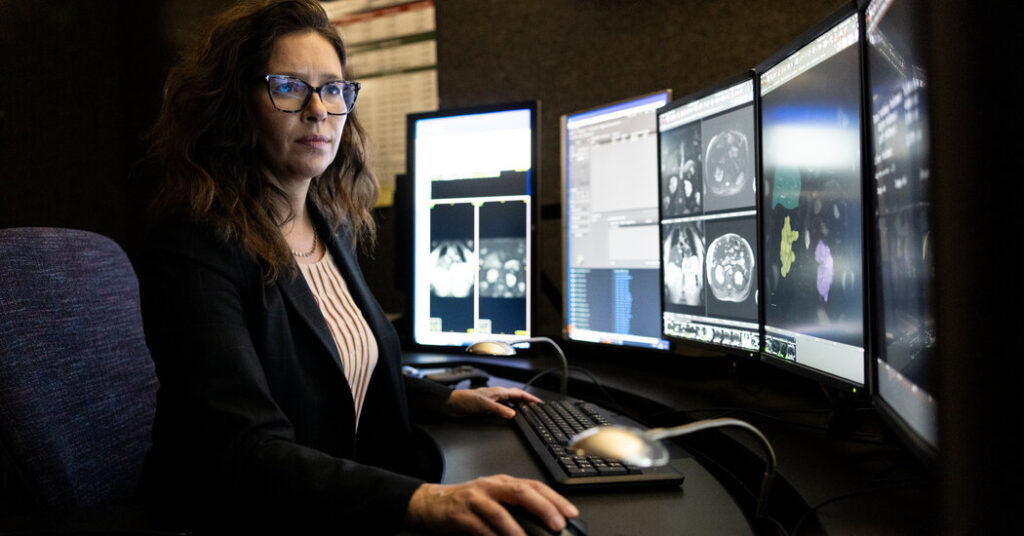

That team works with specialists like Dr. Theodora Potretzke, who focuses on the kidneys, bladder and reproductive organs. She describes the radiologist’s role as “a doctor for other doctors,” clearly communicating the imaging results, assisting and advising.

Dr. Potretzke has collaborated on an A.I. tool that measures the volume of kidneys. Kidney growth, when combined with cysts, can predict decline in renal function before it shows up in blood tests. In the past, she measured kidney volume largely by hand, with the equivalent of a ruler on the screen and guesswork. Results varied, and the chore was a time-consuming.

Dr. Potretzke served as a consultant, end user and tester while working with the department’s A.I. team. She helped design the software program, which has color coding for different tissues, and checked the measurements.

Today, she brings up an image on her computer screen and clicks an icon, and the kidney volume measurement appears instantly. It saves her 15 to 30 minutes each time she examines a kidney image, and it is consistently accurate.

“It’s a good example of something I’m very comfortable handing off to A.I. for efficiency and accuracy,” Dr. Potretzke said. “It can augment, assist and quantify, but I am not in a place where I give up interpretive conclusions to the technology.”

Down the hall, Dr. Francis Baffour, a staff radiologist, explained the varied ways that A.I. had been applied to the field, often in the background. The makers of M.R.I. and CT scanners use A.I. algorithms to speed up taking images and to clean them up, he said.

A.I. can also automatically identify images showing the highest probability of an abnormal growth, essentially telling the radiologist, “Look here first.” Another program scans images for blood clots in the heart or lungs, even when the medical focus may be elsewhere.

“A.I. is everywhere in our workflow now,” Dr. Baffour said.

Overall, the Mayo Clinic is using more than 250 A.I. models, both developed internally and licensed from suppliers. The radiology and cardiology departments are the largest consumers.

In some cases, the new technology opens a door to insights that are beyond human ability. One A.I. model analyzes data from electrocardiograms to predict patients more likely to develop atrial fibrillation, a heart-rhythm abnormality.

A research project in radiology employs an A.I. algorithm to discern subtle changes in shape and texture of the pancreas to detect cancer up to two years before conventional diagnoses. The Mayo Clinic team is working with other medical institutions to further test the algorithm on more data.

“The math can see what the human eye cannot,” said Dr. John Halamka, president of the Mayo Clinic Platform, who oversees the health system’s digital initiatives.

Dr. Halamka, an A.I. optimist, believes the technology will transform medicine.

“Five years from now, it will be malpractice not to use A.I.,” he said. “But it will be humans and A.I. working together.”

Dr. Hinton agrees. In retrospect, he believes he spoke too broadly in 2016, he said in an email. He didn’t make clear that he was speaking purely about image analysis, and was wrong on timing but not the direction, he added.

In a few years, most medical image interpretation will be done by “a combination of A.I. and a radiologist, and it will make radiologists a whole lot more efficient in addition to improving accuracy,” Dr. Hinton said.