On an early summer day in 1876 near Druid Hill Park in Baltimore, a middle-aged woman carrying three large, putrid mushrooms repulsed fellow travelers riding a horse-drawn trolley car.

Even wrapped in paper, the stench of the aptly named stinkhorn mushrooms was overpowering, but the woman stifled a laugh upon overhearing two other passengers gripe about the swarm of flies around them. The smell didn’t bother her. All she cared about was getting the specimens home to study them, she would later write.

This was Mary Elizabeth Banning, a self-taught mycologist who, over the course of nearly four decades, conducted seminal research on the fungi of her state, Maryland.

Miss Banning characterized thousands of specimens that she found in Baltimore and the surrounding countryside, identifying 23 species new to science at the time.

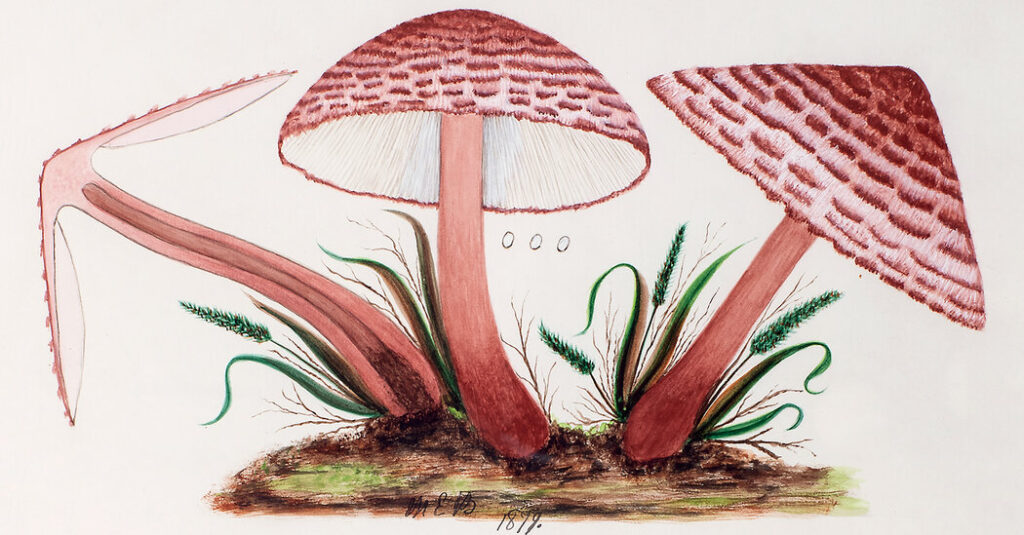

A gifted artist, she collected these observations into a manuscript called “The Fungi of Maryland.” It consisted of 175 stunning watercolor plates, each an accurate yet intimate portrait of a given species, along with detailed scientific descriptions and anecdotes about collecting the mushrooms.

The manuscript was Miss Banning’s life’s work, and she yearned to see it published. But it ended up in a drawer at the New York State Museum in Albany, forgotten for almost a century.

A selection of her watercolors makes up the backbone of an exhibition at the museum that opened this month and runs until Jan. 4 of next year. The exhibition, called “Outcasts,” recognizes Miss Banning’s long-overlooked scientific legacy as well as the museum’s mycology collection, which is one of the most historically significant in the country, according to Patricia Ononiwu Kaishian, the museum’s mycology curator, who conceived the exhibition.

Miss Banning called fungi “vegetable outcasts.” Back then (and all the way until 1969) fungi were classified as a peculiar type of plant. Most botanists from the mid-19th century viewed their study as a research backwater.

Miss Banning herself was an outcast. “She wanted very much to be part of the scientific community,” said John Haines, who was the museum’s mycology curator until he retired in 2005 and who has extensively researched her history. But as a woman living in the 19th century, that path was largely closed to her.

Similar to contemporaries such as Beatrix Potter, who also sought to make her mark on the emerging field of mycology, “the sentiment was, ‘Well, you go home and make your pictures,’” Dr. Haines said.

One scientist did give her the time of day: Charles Horton Peck, who worked at the museum as New York’s first state botanist from 1868 to 1913. Mr. Peck, a pre-eminent figure in American mycology, dedicated most of his career to fungi, collecting more than 33,000 specimens in surveys across New York and describing more than 2,700 new species in his annual reports.

“A lot of the fungi that people recognize from New York or from the Northeast are ones that Peck described,” Dr. Kaishian said.

Miss Banning first wrote Mr. Peck in 1878, asking for feedback on her manuscript. Unlike other scientists she had tried to contact, he wrote back, and they corresponded for nearly 20 years. Her letters, some of which are exhibited, offer a window into their relationship.

“You are my only friend in the debatable land of fungi,” she wrote to him in 1879. She chronicled her collecting forays and scientific observations, and relayed her dreams for the manuscript. “I have a powerful will,” she wrote in 1889. “I have made up my mind to brave defeat sooner than not make an effort to have the plants of Maryland published.”

Miss Banning’s letters were often whimsical and passionate. None of Mr. Peck’s letters to her remain, but his tone in other letters suggested he was much more restrained. Nevertheless, he treated Miss Banning like a respected colleague — offering her scientific mentorship, publishing descriptions of species with her support and even naming species after her. Their scientific bond was undeniable.

“This is a love story, but not between the two people — they were both in love with fungi,” Mr. Haines said. A play he wrote about their relationship drawing from Miss Banning’s letters will be performed at the museum on April 4 at a gallery opening event for the exhibition.

Love triangles, though, are especially prone to turning sour. With no publishing prospects of her own in sight, Miss Banning sent her manuscript to Mr. Peck in 1890, hoping that he could publish it. “He would have had the resources to make it a permanent part of the mycological record,” Dr. Kaishian said. But he never did.

Although she expressed how difficult it was to part from the work and begged him to reassure her that he appreciated its contribution to the field, she did not receive such recognition. “It seems to me by her letters that she died without really understanding the legacy, the value of her work,” Dr. Kaishian said.

In one of her last letters to Mr. Peck in 1897, six years before she died, destitute and alone in a rooming house in Virginia, Miss Banning lamented the book’s loss. “I hardly know how I ever came to part with my illustrated book,” she wrote. “To tell you the truth, I long to see it and call it my own once more, but this could never be.”

“That just still brings tears to my eyes,” Dr. Haines said.

It was Dr. Haines who originally brought Miss Banning’s manuscript to light.

An eccentric curator showed it to him when he visited the museum for a job interview in 1969. He recalls being dazzled by the colors, which were superbly preserved by the fact that the pages had not been open to sunlight for decades.

He exhibited some of the paintings in 1981, and they were shown a few more times, including in Talbot County, Md., where Miss Banning was born. With the help of this spotlight, Miss Banning was inducted into the Maryland Women’s Hall of Fame in 1994. But since the mid-1990s, in part because the pigments degrade quickly in the light, the pictures had been packed away.

Beyond Miss Banning’s work, “Outcasts” gives visitors a glimpse into the broader historical context of mycology. “Fungi are enormously critical organisms that, going back hundreds of millions of years, have shaped the very texture of the earth,” Dr. Kaishian said. “But their stories are still mysterious and often neglected.”

In addition to Miss Banning’s watercolors and letters, the exhibition includes a host of other artifacts and experiences. Visitors can explore one of Peck’s microscopes and mushroom specimens collected by Miss Banning as well as ones collected recently by Dr. Kaishian, or marvel at a set of strikingly realistic wax sculptures of New York fungi made for the museum in 1917 by an artist, Henri Marchand, and his son Paul.

Murals made by museum artists illustrate the biology of fungi, the role they play in the ecosystem and their evolutionary history. A rare fossil of Prototaxites, a 30-foot-tall fungus that lived during the Devonian period about 400 million years ago, points to just how significantly the Earth has changed over time.

Overall, Dr. Kaishian said she hoped that the exhibition demonstrated why natural history collections like this one deserve public support and preservation.

The 150-year-old specimens hidden in cabinets that visitors rarely see help scientists map the limits of different organisms, both geographically and genetically — and that makes it possible to document changes to biological diversity in the face of climate change, for example.

“Natural history collections are active repositories for contemporary research,” Dr. Kaishian said. “There needs to be a lot more science communication about what goes on here and why it matters.”

https://www.nytimes.com/2025/03/25/science/mushrooms-fungi-new-york-state-museum.html