Without access to the site, it may be quite some time before outside experts can gauge exactly how seriously Fordo was damaged, though a recent U.S. assessment described it as badly damaged. But a look at the bomb used and the facility’s structure, as well as an assessment of the site’s geology, offers some clues.

The bomb

Ballistics and blast experts describe the GBU-57 as akin to a giant bullet. Dropped from a B-2 bomber, the 30,000-pound bomb, which includes more than 5,000 pounds of explosives, hits the ground at around supersonic speed before detonating.

As powerful as it is, even a bomb like the GBU-57 is not certain to destroy a hardened target buried deep in the rock of a mountainside, experts say.

A rough estimate shows that a 30,000-pound projectile moving faster than the speed of sound would travel at most five to 10 meters — up to around 35 feet — into several common types of rock, including those most likely found at Fordo, said Ryan Hurley, an associate professor of mechanical engineering at Johns Hopkins and an expert on the behavior of rocks in extreme conditions. Most estimates put Fordo’s depth at somewhere between 260 and 360 feet.

Fractures left by the first blast could allow subsequent bombs to reach deeper, but just how far is hard to predict.

Mr. Hurley and other experts said that a precise calculation of the damage was impossible without advanced computer simulations, classified data on real-world tests, the exact speed and shape of the bomb, and extensive knowledge of Fordo’s structure and the geology of the site.

The ventilation shafts

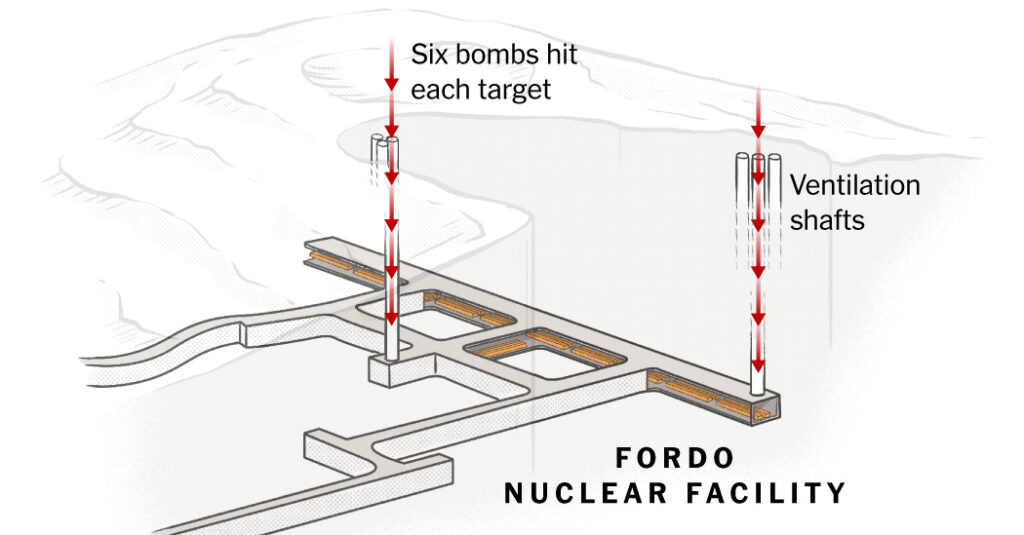

When the strike planners looked for vulnerabilities in Fordo’s structure, they zeroed in on the ventilation shafts that open to the mountainside above the bunker, which would allow them to avoid trying to blast their way through the hard rock above the facility.

The main shafts did not go straight down, said a Defense Department official familiar with the decision making, who spoke on the condition of anonymity to discuss operational matters. They zigged and zagged somewhat at the top, meaning that the path to the bunker was not a straight shot until toward the end.

The exact shape of the ventilation shafts was unclear, but angles would mean the bombs would encounter a combination of rock and open tunnels. Planners decided that they would need multiple bombs.

Each of the shafts opened to a trident shape at the top, according to a June 26 Pentagon briefing. In both locations, the aim was to blow off a concrete cap with one bomb and drop five more down the main shaft.

The geology

The damage that a GBU-57 — or a succession of them — causes depends on the geology at the point of impact.

Several geologists consulted by The New York Times said that an Iranian survey of the Fordo area, published in 2020 in Geopersia, an academic journal from the University of Tehran, indicates that the rock there consists largely of ignimbrite, a type of volcanic rock.

“Ignimbrite is a great thing to dig into,” said Yizhaq Makovsky, a geoscientist and associate professor at the University of Haifa in Israel. He said that the ancient, subterranean dwellings in Cappadocia, in central Turkey, were carved into ignimbrite. Some of those structures have multiple levels, connecting tunnels and hundreds of entrances.

The precise grade, or hardness, of the ignimbrite around Fordo is unclear, Professor Makovsky said, but as in Cappadocia, the material probably made it easier to build an underground bunker. Visually, the ignimbrite around Fordo appears to be relatively soft, he said, but closer study would be required to be certain.

Ignimbrite offered another advantage for the Iranians, he said. Because it is relatively porous, it may act to tamp down damaging shock waves, like those from the American bombs. In that way, he said, ignimbrite may act like “sacks of sand around old forts, put up to stop the bullets.”

Nick Glumac, an engineering professor and explosives expert at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, said there was little doubt about the cushioning effect of ignimbrite, or volcanic tuff.

“Tuff is well known in the blast community as a very efficient absorber of energy — one of the absolute best,” Professor Glumac said. “Porous materials like that are used in many applications to limit the damage zone associated with blast from a high explosive.”

The facility

The Fordo complex also had multiple stories, the Defense Department official said, increasing the number of bombs the United States calculated it needed to use to destroy the centrifuges and other equipment.

And the bunker could have been protected in other ways.

Iran is a major producer of concrete, and Iranian researchers have published papers on concrete mixed with minuscule steel fibers and other strengthening materials. By forming a bridge across tiny cracks when the concrete is stressed, the fibers can make concrete more resistant to blasts or impact, said Clay Naito, a professor of structural engineering at Lehigh University whose research focuses on the performance of reinforced concrete.

“The use of fibers can double or triple the tensile strength, and allow the cracks to remain stable,” Professor Naito said. “That keeps the concrete together to a much greater extent.”

How much it helps depends on the power of the blast and the specific mix of concrete, he said. It’s unclear whether the Iranians put this material into Fordo, but he said it had become routine in the United States to spray concrete on the inside of tunnels with steel fibers as a layer of protection and structural support.

More elaborate approaches might involve steel plates to help absorb the shock of an explosion or keep concrete shards from flying off the walls and damaging equipment or injuring personnel.

Some of the protective measures in place at Fordo are known. Inspectors from the International Atomic Energy Agency have over the years described thick-walled chambers separated by heavy, blast-resistant doors.

The variables

So, how badly was Fordo damaged? A lot depends on how close to the facility any of the bombs detonated. But with so many variables — and so many unknowns — it may be difficult to ever really be certain.

The bombs probably did not reach the centrifuge chambers themselves, although analysts are still conducting detailed assessments, the Defense Department official said. The goal, the official said, was to use the shock waves and other effects of the explosions to destroy the centrifuges.

If the bombs did not reach the bunker itself, the explosions could still have caused major damage if they took place just outside it or in a ventilation shaft.

In that case, there would be some structural damage where the shock waves hit. “And then as we get into the broader tunnels and further out, it’s having a damaging effect on equipment,” said Andrew Nicholson, a director of Viper Applied Science, an Edinburgh-based company that develops blast simulation software and studies the effects of extreme loads on structures.

If one or more bombs did manage to reach the bunker, the damage, however significant, might still be limited.

“I would think it would toast everything pretty substantially,” said Peter McDonald, another director at Viper.

But as devastating as a blast in the confined space of the bunker would have been for the equipment, Mr. McDonald added, he would not expect a full collapse of Fordo. Structural damage would most likely be limited to areas near the explosion.

Damage depends on where the bombs detonated

Professor Hurley, the Johns Hopkins mechanical engineering expert, said that the Pentagon’s overall approach appeared to have been sound.

“I would say that if they studied the geology and ventilation shafts as carefully as reported, then it’s likely that they did very significant damage,” he said.

That’s consistent with the growing confidence of American officials that the strike badly damaged Fordo and wiped out its array of centrifuges.

But Jon B. Wolfsthal, the director of global risk at the Federation of American Scientists and an arms control official in the White House during the Obama and Biden administrations, said that how much the U.S. strike on Fordo set back Iran’s nuclear program would depend on precisely how the shock waves and other effects of the blast tore through the bunker.

“If it’s a shock wave,” Mr. Wolfsthal said, “there’s a lot of things there that are being recovered. If it’s more of a fiery blast, and everything’s been destroyed, there’s probably very little. But until we know that, I can’t do an effective calculation for how much might be left and how much can be salvaged.”

https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2025/08/20/world/middleeast/fordo-us-iran-nuclear-program-strike.html