This transcript was created using speech recognition software. While it has been reviewed by human transcribers, it may contain errors. Please review the episode audio before quoting from this transcript and email [email protected] with any questions.

- archived recording 1

-

Love now and always.

- archived recording 2

-

Did you fall in love last night?

- archived recording 3

-

Just tell her I love her.

- archived recording 4

-

Love is stronger than anything you can feel.

- archived recording 5

-

[SIGHS]: For the love.

- archived recording 6

-

Love.

- archived recording 7

-

And I love you more than anything.

- archived recording 8

-

(SINGING) What is love?

- archived recording 9

-

Here’s to love.

- archived recording 10

-

Love.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

From “The New York Times,” I’m Anna Martin. This is “Modern Love.” Every week, we bring you stories about love, lust, longing, all the messiness of human relationships. This week, I’m talking to the country singer Orville Peck.

- archived recording (orville peck)

-

(SINGING) See

See the boys as they walk on by

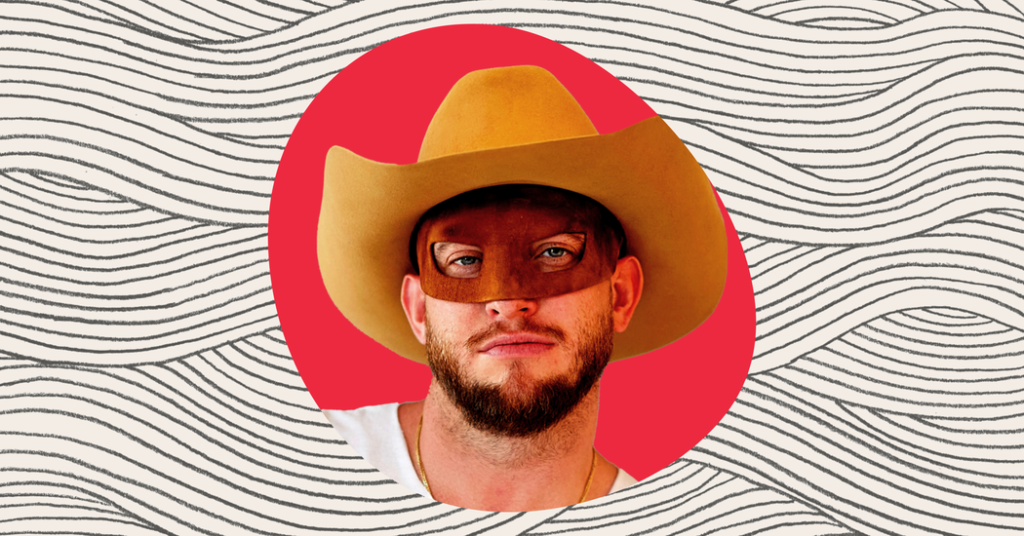

Orville is kind of an enigma. He grew up in South Africa. He uses a stage name. And if you’ve seen pictures of him, you know his signature look is a cowboy hat and a mask. He doesn’t show his face in public. But that’s changing next week because Orville is making his Broadway debut in “Cabaret.” He’s replacing Adam Lambert in the role of Emcee, and he’ll do it without the mask.

I wanted to talk to him because even though his vibe and the mask are so mysterious, his music is kind of the opposite. He doesn’t hide his emotions. Orville is known for writing these haunting, lonely ballads, and he told me a lot of them are about his real life.

- archived recording (orville peck)

-

(SINGING) It ain’t the letting go

It’s more about the things that you take with

Uh-huh

And I can feel it getting closer

With every kiss

There’s so much yearning in Orville’s songs. And yet they’re still so romantic. He blends these feelings of both love and pain in a way that just feels true.

- archived recording (orville peck)

-

(SINGING) Don’t want to wash you away

I swear there’s good things

That are coming your way

And I can’t be the one left here

Dragging you down

Letting you drown

[MUSIC PLAYING]

Today, Orville and I talk about why love can sometimes feel so painful. He reads a “Modern Love” essay about love addiction and what it took for the author to realize what she thought was love was actually hurting her. And Orville tells us about his own moment of realizing the same thing.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

Orville Peck, welcome to “Modern Love.”

Thank you. Thank you for having me.

Thank you for taking the time. I’m going to start with a mask question, which I feel like, kind of, everyone does in interviews with you. But I know you’ve actually made a big decision about your mask. You’re not going to wear it on stage for your role as Emcee in “Cabaret.” And I want to know, like, how does that feel, the vulnerability of the public, the audience actually seeing your face?

I’m terrified.

Really? Really?

Of course. I mean, it’s so silly, but it’s making me realize — because in a lot of ways, I forget. I even forget I’m wearing it right now.

Wow.

I’m so not conscious of it any longer. It’s like me putting on eyeliner or whatever the fuck, you know? Can I swear on this?

Yes, you can.

Great. I cuss a lot. So it’s like, for me, I don’t even think about it anymore. But now, suddenly, I’m thinking about it. I’m in two minds about it. On one hand, I’m really nervous because I just haven’t performed without it in a long time.

How long have you been wearing it as a performer?

Almost 10 years.

Oof, OK.

Yeah. It’s real smelly under here. Just kidding.

[LAUGHS]:

But no. So but on the other hand, I’m also, like I said, I’m playing a character in this show. So it almost feels like I’m not showing myself still.

Hmm. I mean, I want to talk also about your music a little bit because that’s an area where you do show a lot of yourself. You are a country singer. And so much of your music exists in this kind of mix of romance and longing, but also, quite frankly, a lot of pain. These are themes that you return to very often in your songs. And I wonder, do you think there’s something specific about country music that allows you to express this mix of feelings altogether?

Oh, my God, absolutely.

Yeah?

Yeah. I think it’s what drew me to country music, honestly. I mean, I think one of my first loves of country was Patsy Cline.

I feel like every song of hers was about yearning. I mean, “Walkin’ After Midnight,” to me, that’s like the gay experience. It’s like, walking alone at night, wishing someone could love you who won’t love you.

- archived recording (patsy cline)

-

(SINGING) After midnight

Out in the moonlight

Just like we used to do

I’m always walking

After midnight

Searching for you

That is country music in a nutshell to me — I mean old country, specifically. New country, I don’t know what they’re singing about in new country.

[LAUGHS]:

Like trucks and whatever the fuck they’re singing about. But old country, for sure. It’s about yearning, unrequited love, loss, disappointment, inadequacy. I mean, there are themes that are very, I mean, I think relatable to a lot of people, and specifically, a lot of othered people, you know, people that are outsiders.

It strikes me that hearing this lonely, longing, yearning music — Patsy Cline’s, yours — it feels good, though. It’s like, these painful emotions, as a listener, it feels good to hear them.

Yeah. Well, we have that crazy human condition where —

years ago, someone tweeted or something. There was something going around where it was like, you know when you’re 16 and you’re rewinding the song to the heartbreaking part because you didn’t cry hard enough?

Yes.

[LAUGHS]: That is so relatable to me. And I think you feel release, right? That’s the beautiful thing about art, is like, it does that, right? It releases an emotion that we’re yearning for. It’s all yearning, you know?

God. I will tell you, I mean, that was me. That was me on YouTube with Bon Iver’s “Skinny Love.” It was “Skinny Love.” Like every other person at that time, it was “Skinny Love.” What was your “I’m going to cry” moment for you?

Oh, my God, I have such a long list. Any kind of heartbreaking song – I mean, I still listen to Dolly Parton’s “I Will Always Love You.”

- archived recording (dolly parton)

-

(SINGING) And I

Will always love you

I mean, it has never not hit that spot for me, maybe even more as I get older. I’m like, it is just — that is the perfect song in the world, I think, because you’re saying goodbye to someone who you love. You’re not saying goodbye because you hate them or because they fucked up.

You’re saying goodbye and wishing someone the absolute most luck and love in the world because you care about them so much, and you cannot be with them. I mean, that is love, you know? That’s the reality of what you deal with in relationships, you know?

So what you just said about “I Will Always Love You” really reminds me of the “Modern Love” essay you picked to read today. It’s about a lot of those same things. The essay in particular is about love addiction. It’s called “Strung Out on Love and Checked In for Treatment” by Rachel Yoder.

And in it, the author, Rachel, does have to say goodbye to someone she feels quite intensely for, but that she has this relationship with that causes her distress and, quite frankly, causes a lot of destruction in her life. And just to tee it up, I’m going to ask you a sort of big question, which is, why do you think love and pain are so often intertwined?

I think in my experience with it, because I actually have a lot of experience with this topic — I’m a recovering love addict myself. And I think the problem is when you are a sensitive person and you somehow feel ostracized, perhaps, you have this sense of yearning. I think this actually happens a lot with queer people.

And I mean, not just queer people, obviously, but from my perspective, I grew up with a lot of yearning. I was always friends with straight boys. I mean, I was out, but all my friends were skaters and punks, and they were all straight boys. And I was always in love with all these guys. And it was like, my whole life was centered around this sort of unrequited love. And I never really developed that sort of healthy relationship to love.

Huh.

Like, my love was always one-sided, and that was sort of my relationship to love and romance. Yeah, I think it’s a very fascinating subject. And I think it’s sort of heartbreaking because at the root of it, I think it’s all about just wanting acceptance and to feel that exchange of love. But a lot of people have never felt it, and so they don’t understand how to even look for it.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

When we come back, Orville Peck reads the “Modern Love” essay, “Strung Out on Love and Checked In for Treatment.” Stay with us.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

“Strung Out on Love and Checked In for Treatment” by Rachel Yoder.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

“In 12-step confessional style, this is what love addiction did to my life. I dropped out of college, quit my job, stopped talking to my family and friends. There was no booze to blame for my blackouts, vomiting, and bed wetting, no pills to explain the 15 hours a day I slept, no needles as an excuse for my alarming weight loss.

I hit bottom one sleepless night, strung out on the bedroom floor, contemplating suicide. And then I spent four months and a good chunk of my family’s money in treatment for love addiction.

I know what you’re thinking. Love addiction? Give me a break. Believe me, I’ve thought it, too. Even now, years later, I have mixed feelings about the term. But the facts of my experience, a relationship that utterly consumed my life, the magnitude of the depths to which I plunged before I sought help, are indisputable.

At the start, our new romance high was unlike any I had experienced. Matt was my knight in shining Mercedes, courageously wielding his credit card as we bushwhacked through the malls of Northern Virginia. We danced barefoot in the grass at a Harry Connick, Jr., concert, and he surprised me with gifts from Tiffany, cunningly stashed in the glove compartment. In Atlantic City, we stayed in the honeymoon suite at the Hilton Inn; in Florida, had an ocean view from the Ritz. Day after day, we lay in his bed, with Sting’s “Fields of Gold” lilting in the background.

But mere weeks into the relationship, our idyllic soundtrack of golden barley fields, cascading hair, and loving promises was replaced by “Every Breath You Take,” played at deafening volume and on eternal repeat. We had crossed some boundary from passion to obsession, and we simply couldn’t stand to be away from each other. Friends, family members, school, and my job became threats, so I left them. Soon, our tunnel of love grew so dark and isolating that I could no longer conceive of a life outside it.

I couldn’t because our relationship, however damaging, was my life. And if it were to end, I didn’t see how I could continue to exist. Things reached a crisis point one night when, after being interrogated by Matt for hours over an old photo he had found of me in the arms of a male friend, I feared he was going to dump me. I spent that night alternating between fantasies of kitchen knives and nagging thoughts I could no longer suppress, telling me that something wasn’t right, that love shouldn’t make me want to die.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

Matt decided he needed professional help and announced he was sending himself to an addiction treatment center all the way across the country in Arizona. Already familiar with the treatment world, Matt knew that what was happening between us was dire. He even gave me a book on love addiction to bring me up to speed.

Faced with the prospect of being left in his apartment during that gray March without him or anyone, I decided I would get professional help, too. I wanted to prove to Matt that I was a good girlfriend, worthy of his love. Going to treatment, I reasoned, was the ultimate evidence of this. I went online and I found a center that was unsurprisingly also in Arizona.

But my going to treatment to try to make our relationship work was like an alcoholic checking herself in so that she could learn how to drink. I couldn’t see that the solution wasn’t learning how to live with Matt, but learning how to live without him.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

I arrived at the center, toting my oversized suitcase, exhausted and 15 pounds underweight, with dark circles under my eyes. Four women, my apartment mates, were watching television in the living room. ‘So what are you here for?’ ‘I’m depressed,’ I said, ‘and, you know, stuff with my family. Maybe alcohol, love addiction. What about you?’ ‘Alcohol,’ she said. Drugs, abuse issues, eating disorders, codependency, depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress, obsessive compulsive disorder, everything.

And she was nothing compared with my roommate, whose mom had been murdered, whose dad had died when she was 18, and who, before the age of 20, had been a stripper and a meth addict. Yet, here I was, at the same place, and all I could really say in response to anyone who asked was, I really miss my boyfriend.

In addition to group therapy, we had to attend a daily 12-step meeting. I tried Alcoholics Anonymous and Narcotics Anonymous, but couldn’t connect with people who talked about booze and drugs when all I wanted to talk about was Matt, Matt, Matt. So I stuck to meetings of Sex and Love Addicts Anonymous.

Time and again, I heard from fellow addicts outlandish stories of vitriolic romances and suicidal tendencies. Crazy, I thought, until I considered how similar their stories were to mine. Because Matt was, in effect, my drug. I wasn’t allowed to speak to him during my first month of treatment. So you can imagine my psychotic delight when I returned to my apartment one afternoon at the end of that month to find his voice cooing from the answering machine, ‘It’s me, your boyfriend, Matt.’

These words might as well have been high-grade heroin. I wouldn’t be surprised if my pupils dilated. I replayed it once, twice, 10 times, in a euphoric trance. The reason for Matt’s call was to invite me to his treatment center for our very own family week. His undying love for me was confirmed when I discovered that I got a week alone with him, no other family members, just us. I imagined our teary reunion, big-hearted acknowledgment of wrongdoing, non-accusatory I-statements. But on an April afternoon, in the middle of the Arizona desert with both of our therapists present, Matt finally dumped me.

I’d never entertained the thought that we might actually break up for good. I erupted into hysterics and looked to Matt, desperate for some sign that this was all a big mistake. He merely stared at his palms, then at me blankly. ‘These are the painful consequences of your actions,’ his therapist said to me sternly. ‘You should be thankful to Matt for helping you get here.’

Thankful? No. I raged through the hallway, slamming doors and spewing profanity, then collapsed into fits of malevolent despair, only to be ushered to shady cots throughout the center. I insulted all who implored me to calm down. Back at the motel, I vomited and then endured a night of cold sweats in endless half-dream delirium in the blue light of late-night TV. I woke up with a biting headache and soon developed an embarrassing twitch.

Since I no longer had Matt’s approval and our ultimate reunion as motivation for my recovery, I was forced to consider how I might instead get better for my own sake and started to do all those charmingly neurotic things that you see in the movies about rehab. I took up kickboxing, crocheted an afghan the size of Rhode Island, and ate many, many cookies. I watched “Blind Date” religiously, got a job waitressing, developed a crush, and made plans to finish college.

Perhaps most important, I even got rid of my drug’s last residue, Matt’s message. I listened to it over and over — ‘It’s me, your boyfriend, Matt.’ ‘Your boyfriend, Matt.’ ‘Your boyfriend’— until one day, when I finally, unceremoniously, erased it.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

Six years and three relationships later, I am still coming to terms with this experience. For a long time, I resented Matt, blamed him for my life’s falling apart, and could not see myself as anything other than a victim. But now I truly feel grateful to him for ending our relationship when I couldn’t, for making the difficult choices that he knew in the long run would help both him and me get better.

A year ago, in an odd twist of fate, I moved back to the Arizona desert to attend graduate school. Those first few months were some of the hardest since treatment, and I wondered how, after six years, I could be back in the same desolate place, feeling much the same way.

With my move, I had ended a relationship. And aware of my tendency to numb my heartache with new heartthrob, I put myself on a no-dating plan reminiscent of my treatment days. But in a moment of weakness, I completed and posted an online dating profile, and soon, my inbox was filled with email messages from men, each one a little hit for my addiction. But the high wasn’t as fulfilling as it used to be, or maybe I was just too aware of the potential consequences.

So I deleted the profile and put my no-dating plan back on indefinitely. I don’t want my next relationship to be an act of addiction. I don’t want to partner up because of some compulsive need. I want to do it right. And for now, that means not doing it at all.”

[MUSIC PLAYING]

We’ll be right back.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

Orville, what’s going through your mind now that you’ve read the essay?

Yeah. I mean, I think, as I said, I have a lot of firsthand experience with addiction of a lot of kinds and also recovery from those addictions. And where she ends off, I think, is relatable because I think, ultimately, when you’re an addict, for me, the drug of whatever that is, it’s not about that, you know?

I’m a recovering alcoholic. I’m a recovering addict. For me, it’s not even really about not drinking. It’s about dealing with all of the reasons why you drink to cope, right? It’s like everything else. Not drinking is like the easiest part. That’s the first part. You know what I mean? That’s like the essential first step.

But it’s everything else, you know? And I think she went to recovery thinking, like, oh, I’m going to go save this relationship and save that thing. And really, what she took from it is, like, well, oh, actually, it’s actually got nothing to do with this relationship. It’s actually got nothing to do with this person. It’s got nothing to do with anything, except for, I need to sit down and ask myself, why does this form of validation make me feel complete? What’s missing within me, you know?

You said that you had some experience with love addiction. And I guess, in your experience of that, what was the validation you were chasing in your experience of —

Yeah. I think growing up, like I said, I never really — I never had relationships. And I think — hopefully, this is changing now, but in my generation and before, I think a lot of queer people don’t hit the milestones that a lot of people hit growing up, you know? I never got to have my first kiss be something sweet and meaningful. It was like traumatic because then you’re scared, you know?

And my first crush was on someone that I couldn’t even tell anyone about because I was terrified of kids knowing I was gay, you know? I didn’t develop very positive connections to what loving someone was. And I didn’t realize how much that had seeped into my adult life. A lot of my first relationships, I really just, like — not even consciously. I just truly believed that I was not enough. I had to make someone love me, right?

So then love becomes this — it’s not an even partnership. It’s not an even exchange. It’s heavily weighted in one area, and you’re also giving someone your total power. And I’m not talking power in, like, a sort of — I mean, your power of self.

Yourself. Your sense of self.

Yeah. And so I did that a lot.

Can I ask you, is there a specific moment or just even image of yourself that’s coming to mind when you’re speaking about, I was craving this validation? I was trying to get this love. It was transactional. Is there a moment in your life that you can share that you’re thinking of when you’re speaking about this?

Yeah. I mean, this unfortunate chain of events and way of developing that part of myself into my adulthood, it eventually landed me in a really awful relationship that was very abusive and for a long time. And it’s so interesting because people hear about a relationship like that, and I feel like the snap judgment — and this is me included, even at that time — is like, well, why don’t you leave? Like, why are you subjecting yourself to this, right?

But that’s where the sad thing about this kind of yearning and this love addiction comes in, is that at that point, you’re so relieved to have somebody love you and to have this feeling of being chosen, you know? It’s like, goes beyond seen. It’s like, I never felt chosen. Yeah, you know? And I think that kind of mentality, it makes you stay in a bad situation because the feeling of being with someone starts to feel more important than the feeling of actually being truly happy or loved.

Oof.

It’s so sad.

Oh!

[LAUGHS]:

I mean, I really — you’re articulating it beautifully and really heartbreakingly. How did you recognize that it was time to get out? I mean, for Rachel, it’s like, Matt, her boyfriend, enters treatment, and she kind of does it just to be with him. But what was your moment of perhaps recognizing the dynamic and knowing you needed to escape it?

Someone I knew had been in a really toxic and abusive relationship, and they basically broke it off. And he had mentioned a term to me at the time that I’d never heard before that he had never heard before either, but their therapist kind of brought up or whatever. And it’s like narcissistic personality disorder, which now I feel like is such an overused term, and everyone’s a narcissist now, you know?

It’s in the culture. It’s in the culture.

It’s like a TikTok term or something. But when it’s an actual — in the actual, serious sense of the diagnosis of that with people, I never heard of it. And so I looked it up, and I was like, oh. It dawned on me. I was like, this is exactly what I’ve been struggling with for the last few years of this relationship. This is who I’m dating.

And so then I stayed in it, though, for years, even after that discovery, knowing that I was in an abusive and shitty situation. And then it kind of all came to a head at some point, and something in me made me just walk out the door in the middle of this crazy, crazy situation that was going on, just walk out the door in the middle of the night. And I walked to my parents’ house.

Wow.

Yeah. I really viscerally remember it because it must have been, like, 3:00 in the morning. It was like pouring rain. And I was —

Of course, it’s raining.

Yeah. And but —

Life does that.

But everything in my body was telling me like, what are you doing? You’re never going to be able to explain this. I think a lot of times, being in an abusive situation, you are spending most of your time defending and cleaning up after your partner and defending them to your family, your friends, and making excuses for them, lying for them, apologizing for them.

And I remember feeling, when I was walking, like, you’re never going to be able to explain this. How are you going to explain this to your parents that why are you here at 3:00 in the morning? What is happening? What’s going on?

Were they awake? Did you have to wake them up?

Yeah, I had to wake them up and went up to their apartment. And I had to basically say — because they were like, what’s going on? And I basically had to say, I think I’m in an abusive relationship. And I just broke down and cried because I’d never said the words before. And my mother held me.

And I think — nobody I told, from that day on, including my parents — I had never met a single person that I told to that was surprised. And so I think it was like relief for them as well because I knew that they were really, really worried about me for a long time because also, it changes you. I was like a different person. mean, that’s why I’m laughing in between explaining this because I’m so far from this now, and I’m so myself again. But you completely lose yourself. It’s like that tunnel of love she’s talking about. I mean, I know I’m talking specifically about a situation like this that turns abusive.

But the thing that is dangerous about this kind of yearning or romanticism or love addiction, whatever you want to call it, the thing that’s hard about being a person like that is that if someone can see that that is your Achilles heel, to be loved, all that person has to do is show up and breadcrumb love to you, and you’re fucked. You’re trapped, you know?

Yeah. But I also feel like you are speaking to us from a place of — you said, right now, you’re maybe in the best place you’ve been —

Definitely.

— in ever?

Ever, ever.

So I mean, I know this is years of, as we’ve spoken about, but what is something, like a concrete thing that has changed in the way you live your life? Maybe it’s like, you’d spoken about how it felt so good to be chosen by someone else. And I guess I wonder, how have you worked on choosing — cheesy, sorry —

No.

— but choosing yourself?

It totally sounds cheesy, but it’s completely accurate. And most cheesy things are.

To me, I felt like loving myself, that idea felt like such an impossible ask. I felt so — really, what it was, I think, angry at myself that why didn’t I develop these things as a kid? So I’m essentially bullying the child within me for years, you know?

And when I started to think of it like that, I started to picture — I have a niece, and she’s like 8. And I started to picture, that’s who you’re being mean to. Look at her, and imagine that’s who you’re being mean to when you speak to yourself this way or when you’re judgmental of yourself.

That was my internal dialogue for the last 30 years of my life, you know? I have really changed that. That was a huge shift for me, being aware of how I speak to myself in my head. That was a massive, massive shift for me. There’s little things, but it takes a long time. I mean, I really — it’s crazy. I’m talking like, just in the last year or two, I feel like I’ve really been able to truly just feel like I really love myself.

I mean, you’re talking about speaking to your younger self with kindness. And you shared that moment, this moment of real rock bottom, walking from the ex, let’s say, to your parents’ house. And I guess I wonder, if you could say something to that version of yourself now, what would you say?

[SIGHS DEEPLY]:

[CHUCKLING]

I think just like —

it sounds so cheesy once again, but I think just that this gets better. I know that sounds so overused, but I think when you’re in something, whatever that might be — and this isn’t even — this is for anything, really. When you’re struggling with something in your life, I think it’s so hard to imagine that anything could feel better again. I think we, as humans, unfortunately become so fatalistic and ultimate about these things.

I’ll feel this way forever.

Yeah, right? I mean, and it’s what keeps people definitely with an addiction, you know? So yeah, I think I would just try to assure that time because I think the hardest thing was like, I just couldn’t imagine a life without this person, even though they were the most negative, and I knew they were the most negative force in my life. I could not imagine what my life was going to be.

And now look at you.

I know. It’s crazy.

And now look at you. [LAUGHS]

On Broadway!

On Broadway!

No, it’s really wild.

Oh, my god.

But you have to know, you got to know it gets better. It’s going to feel better. We are all in control, to some extent, of course, barring a lot of factors out of our control. But for the most part, we are more in control of our happiness than I think we know.

Mm-hmm.

Orville Peck, thank you so much for this conversation. It’s not an easy thing or a simple thing for anyone to come into a studio with a stranger and talk about hard stuff. So I really appreciate you being so vulnerable.

Thank you. I appreciate that. No, it was easy.

And the final thing I’m going to say is it’s so — the mask, crying in the mask —

Oh, my god. I can’t believe I — doesn’t everyone cry on this show? I feel like it’s like —

Everyone cries a little bit. No, everyone cries a little bit. But it’s interesting, we’ve never had someone cry in a mask. So I’m like, the tears go into the mask, and then they go. But it’s also kind of nice because it can be [INAUDIBLE].

I don’t know if I’ve ever cried during an interview.

Oh! Well, that’s kind of cool, though.

Yeah.

No, not cool. I’m grateful.

[LAUGHS]: I think it’s cool.

Orville, let me just say, thank you so much, not just for the tears, but for the conversation.

Thank you. That was a really lovely conversation.

It was so —

Thank you for — yeah, letting me talk about that.

Oh, my god. Thank you for going there.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

This episode of “Modern Love” was produced by Davis Land with help from Amy Pearl. It was edited by Jessica Metzger and our executive producer, Jen Poyant. Production management by Christina Djossa. The “Modern Love” theme music is by Dan Powell. Original music in this episode by Pat McCusker, Dan Powell, Marion Lozano, Elisheba Ittoop, and Rowan Niemisto.

This episode was mixed by Daniel Ramirez with studio support from Maddie Masiello, Nick Pittman, and Catherine Anderson. Special thanks to Mahima Chablani, Noelle Gallogly, and Jeffrey Miranda, and to our video team, Brooke Minters, Felice Leon, Dave Mayers, and Eddie Costas.

The “Modern Love” column is edited by Daniel Jones. Miya Lee is the editor of “Modern Love” projects. If you want to submit an essay or a Tiny Love Story to “The New York Times,” we have the instructions in our show notes. I’m Anna Martin. Thanks for listening.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

https://www.nytimes.com/2025/03/26/podcasts/orville-peck-interview.html