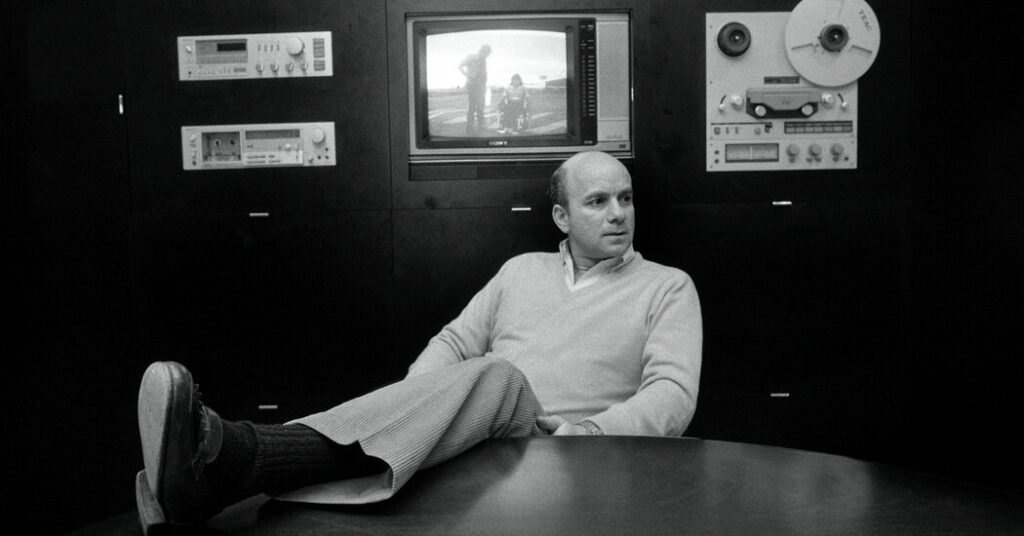

Stanley R. Jaffe, a former Hollywood wunderkind who became president of Paramount at 29, then left after just a few years to become an Oscar-winning producer of films like “Kramer vs. Kramer,” “Fatal Attraction” and “The Accused,” died on Monday at his home in Rancho Mirage, Calif. He was 84.

His daughter Betsy Jaffe confirmed the death.

Mr. Jaffe was known as a hands-on producer, and his work on “Kramer vs. Kramer” (1979), a searing divorce drama, showed why.

The movie was based on a 1977 novel of the same name by Avery Corman, and he bought the rights immediately after it was published. He persuaded a reluctant Dustin Hoffman to play the father, Ted, and cast the relatively unknown Meryl Streep to play his wife, Joanna.

The film was a commercial and critical success. Along with the Oscar for best picture, it won for best actor (Mr. Hoffman); best supporting actress (Ms. Streep); and best director and best adapted screenplay (both for Robert Benton).

Mr. Jaffe was not quite 40 when he won the Academy Award, but he was already a veteran heavyweight in Hollywood.

He made his mark early, independently producing the film version of Philip Roth’s novella “Goodbye, Columbus” (1969). It was a big risk: He borrowed much of the money; Mr. Roth was not yet a household name (Mr. Jaffe optioned the rights weeks before the publication of the author’s career-making “Portnoy’s Complaint”); and as the female lead, he cast an unknown Ali MacGraw, then a photographer’s assistant trying to break into acting.

His success with the film won Mr. Jaffe a position as an executive vice president at Paramount, in 1969; nine months later, he moved up to president, making him, just a few days shy of his 30th birthday, the youngest studio head in Hollywood.

By most measures, he outdid expectations in his new role, landing marquee films like “Love Story” (1970) and “The Godfather” (1972). But he quickly grew restless at the top.

“It wasn’t that I was afraid we couldn’t maintain the company; it was that at age 30, you shouldn’t know what you’re going to be doing at 50, and I was starting to feel as though I were 50,” he told The New York Times in 1983. “I wanted out.’‘

Back on his own, he produced a string of memorable films, including the comedy “The Bad News Bears” (1976), about a youth league baseball team coached by a grumpy Walter Matthau, and “Taps” (1981), a drama, set in a military academy, that launched the careers of Tom Cruise, Sean Penn and Giancarlo Esposito.

Mr. Jaffe stepped behind the camera to direct the 1983 drama “Without a Trace,” starring Kate Nelligan and Judd Hirsch, about the disappearance of a boy in New York, based on a book that drew inspiration from the case of Etan Patz.

The movie, which focused on the painful family dynamics caused by the boy’s disappearance, highlighted a through line in many of Mr. Jaffe’s films.

“I’m attracted to stories that deal with the family and what it’s like to be a member of that family,” he told The Times, “whether it’s together or apart, given the pressures that are put on it by the outside world.”

Stanley Richard Jaffe was born on July 31, 1940, in the Bronx and grew up in New Rochelle, N.Y. His father, Leo Jaffe, was the chairman of Columbia Pictures, and his mother, Dora (Bressler) Jaffe, managed the home.

His father’s work brought Stanley into contact with Hollywood, but not enough to make him want to follow in his footsteps.

“My only real contact with what my father did was that he could get 16-millimeter prints, so every weekend we would show two or three movies at home,” he told The Times in 1983. “But our house wasn’t frequented by stars. My father’s personal life was his personal life, and it was separate from his professional life.”

He studied economics at the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania, with thoughts of becoming a lawyer.

By the time he graduated, in 1962, those thoughts had passed, and he joined Seven Arts, a production company in Los Angeles that merged with Warner Bros. in 1967.

Mr. Jaffe’s first marriage ended in divorce. He married Melinda Long in 1986. Along with his daughter Betsy, from his first marriage, his wife survives him, as does his son Bobby, from his first marriage; a son, Alex Jaffe, and a daughter, Katie Norris, from his second marriage; a sister, Marcia Margoluis; a brother, Ira; and five grandchildren.

In 1983, Mr. Jaffe and the producer Sherry Lansing founded Jaffe-Lansing, a vehicle through which they oversaw a string of successful films, including the dramas “Fatal Attraction” (1987), starring Michael Douglas and Glenn Close; “The Accused” (1988), with Jodie Foster; “Black Rain” (1989), with Mr. Douglas; and “School Ties” (1992), with Brendan Fraser and Matt Damon.

Mr. Jaffe was set to direct “School Ties” when he was lured back to Paramount as president and chief operating officer of Paramount Communications. Along with the movie division, he oversaw a slew of other properties: Simon & Schuster, the publishing company; Paramount theme parks; Madison Square Garden; and the Knicks and Rangers sports teams.

This time he was based in New York, and as a die-hard fan of his hometown teams, Mr. Jaffe took particular pride in his role in managing Paramount’s sports properties. He could often be found courtside or rinkside at the Garden, and he counted the Rangers’ 1994 Stanley Cup win as a career highlight.

Later that year, though, he was pushed from his position after Viacom bought Paramount. When the company blocked his ability to exercise up to $20 million in stock options, he sued, but a judge dismissed the case in 1995.

Once more independent, Mr. Jaffe produced two films, “I Dreamed of Africa” (2000), about a conservationist in Kenya, with Kim Basinger; and “The Four Feathers” (2002), a war film set in late-19th-century Sudan, with Heath Ledger as a young British officer.

Mr. Jaffe was the consummate Hollywood executive, but he felt a deep personal connection to his films, and suffered when they did not do well.

“I’m very vulnerable to a picture not working because it’s something I really care about,” he told The Christian Science Monitor in 1982. “It’s not just 12 reels or two pounds of film. It’s something I believed in.”