But this year also features El Niño, which arrived earlier this month. The intermittent climate phenomenon that can have wide-ranging effects on weather around the world, including a reduction in the number of Atlantic hurricanes.

“It’s a pretty rare condition to have the both of these going on at the same time,” Matthew Rosencrans, the lead hurricane forecaster with the Climate Prediction Center at NOAA, said in May.

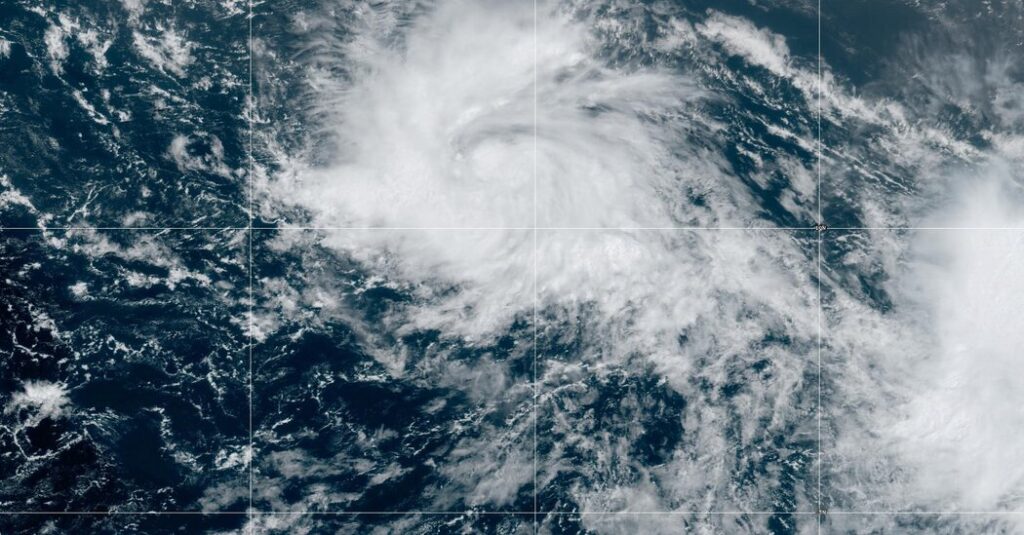

In the Atlantic, El Niño increases the amount of wind shear, or the change in wind speed and direction from the ocean or land surface into the atmosphere. Hurricanes need a calm environment to form, and the instability caused by increased wind shear makes those conditions less likely. (El Niño has the opposite effect in the Pacific, reducing the amount of wind shear.) Even in average or below-average years, there is a chance that a powerful storm will make landfall.

As global warming worsens, that chance increases. There is solid consensus among scientists that hurricanes are becoming more powerful because of climate change. Although there might not be more named storms overall, the likelihood of major hurricanes is increasing.

Climate change is also affecting the amount of rain that storms can produce. In a warming world, the air can hold more moisture, which means a named storm can hold and produce more rainfall, like Hurricane Harvey did in Texas in 2017, when some areas received more than 40 inches of rain in less than 48 hours.

Researchers have also found that storms have slowed down, sitting over areas for longer, over the past few decades.

When a storm slows down over water, the amount of moisture the storm can absorb increases. When the storm slows over land, the amount of rain that falls over a single location increases; in 2019, for example, Hurricane Dorian slowed to a crawl over the northwestern Bahamas, resulting in a total rainfall of 22.84 inches in Hope Town during the storm.